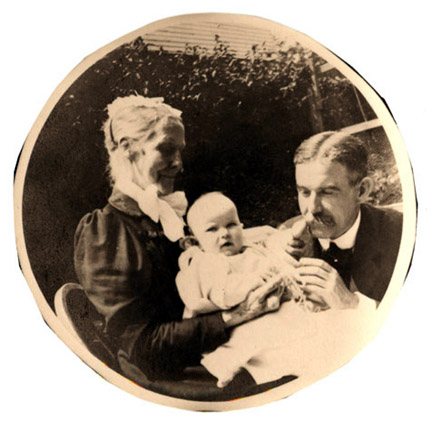

John Wilson Farquhar was born on March 3, 1861, in Chanceford, York County, Pennsylvania. He died 1943, in Easton, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania. Parents were John Fraser Farquhar (1821-1866) and Sarah Wilson.

Education

Lafayette College; Columbia University Law School

Occupation

Lawyer

Marriage

Wife’s name may have been Margaret

Children

- M. Caroline Farquhar, born 08 Dec 1900, in Ossining, Westchester County, New York, died 17 Aug 1987 Easton, Northampton County, PA. At the time of her father’s death, she lived with her father at 312 March Street in Easton, PA. Caroline worked as the secretary to Mrs. William Mather Lewis, wife of the president of Lafayette College.

FAMILY HISTORY LETTER

Only five when his father and grandparents died, John Wilson must have been interested in learning more about his family. To this end he evidently quizzed his mother before her death in 1906. Toward the end of his life, he must have felt a need to write down these memories and to share them with others, particularly his youngest relatives, John Franklin Farquhar and Janet Elizabeth Farquhar, because he wrote a letter to these children on November 19, 1938. I have included it in its entirety because it provides a wonderful description of his family. I like to think that he would have been pleased to know that his great-great grandniece (me) read and treasured his work.

My dear Great Grandnephews and Great Grandniece

I am able to give you recollections of a personal acquaintance with three of your thirty-two great-great-great grandparents and, more fully, of two of your sixteen great-great grandparents. This doubtless is unusual, particularly in respect of your great-great-great grandparents: If at or about my age, 77, you shall have one or more great grandnephews or great grandnieces (or great grandchildren of course) and should write them personal recollections of your grandparents in the Farquhar line, enclosing to them a copy of this letter, they would have at 77 (if I am correct) the attested line of descent, as well as personal knowledge or authentic recollections (if possessed of great grandnephews, great grandnieces or great grandchildren) of twelve generations of the family spanning about three hundred years; and, similarly, births and survivals permitting, the recipients from them of a like letter, fifteen generations and four hundred years.

Your great-great-great grandparent Joseph Farquhar and Margaret Fraser, his wife, lived during their last years with their son and only child, my father, the Rev. John Farquhar, in the Presbyterian Manse at Lower Chanceford, York County, Pennsylvania, where I knew them until their deaths in 1866 in my sixth year. Joseph was a retired stone mason, aged, somewhat bent, very grizzled, tanned and watery of eye from the weather, with Scottish fur in his ears and eyebrows, short, fairly heavy, able to keep himself clean shaven and do light work about the ten acre place, a devout Calvinist. I associate him with chopping rutabagas for the cattle, but remember him best rising heavily from his knees after conducting family worship, thanking God as beseemed the Covenanter he was, that we had “none to molest us and make us afraid” counting “our righteousness filthy rags”?

Margaret, his wife, was slender, tall, straight and quick moving. Her Scottish recollections embraced “the Lady Amelia”, of whom I know nothing further. I remember the bits of candy grandmother Farquhar seemed always to produce for Margaret, her favorite of the five children, and me the youngest, and her little gifts to all of us in celebration of Hogmenay at New Years Eve. She taught us

Rise up good wife and shake your feathers,

Dinna think that we are beggars,

We are children come to play,

Rise up and give us our Hogmenay.and

Tickle ye, tickle ye, on the knee,

If you would a lady be,

You must neither laugh nor cry,

While I tickle ye on the knee.From the letters in cast iron on the ten-plate stove she taught me the alphabet and words of three letters.

Joseph and Margaret came from Aberdeen, Scotland, (where the name Farquhar is familiar) in 1832, with their son John, my father, aged 11, and another John, his cousin, somewhat older (who settled in Boston and prospered, leaving a considerable progeny. He kept a journal of the voyage, which is in the possession of his only surviving child, Nellie, Mrs. Charles H. Furber, 35 Maple Street, Milton, Massachusetts. Strangely the journal makes no mention of the other members of the party. The immigrants landed at Montreal and entered the United States by way of Prescott, on the St. Lawrence opposite Ogdensburg.)

Making their home in Easton, Joseph worked at his trade in the employ of your great-great-great grandfather Alexander Wilson, who also was a stone mason. Some of Joseph’s time sheets were lately in existence. There is a story which from telling I have almost come to believe, that on one occasion hearing someone boast that his grandfather was among the founders of Lafayette College, I said that both of my grandfathers were, for both worked on the foundations, as in fact no doubt they did. “A noble craft, that of a mason”, Scotland has not now his like, wrote Carlyle of his mason father, “good building will last longer than most books–than one book in a million.”

The third of your thirty-two great-great-great grandparents whom I knew was Margaret Wilson, my mother’s mother, wife of Alexander above mentioned. She was a McElroy, and her people were of this Pennsylvania Dutch region, to the southward, I understand. I believe she spoke the language; some phrases, I know, she used, though possibly in banter, as my mother did. I knew her at Easton after we had moved there in 1867 following my father’s death. Margaret had married Alexander Wilson, her senior by twenty-five years, bore him twelve children and raised her family in a tiny house on North Fourth Street, next door to the home, in my time, of the Wikoff family (one of whom, Colonel Wikoff, was the highest ranking American officer killed in the Spanish-American was of 1898.) Margaret’s was a lively household of three or four sons and the rest handsome daughters, active in choir and other church work, with beaus among the Lafayette College students. Alexander had died before we moved to Easton and I never knew him. Margaret I remember as a very small, pudgy person of a most sunny disposition. A twinkle at the corners of her mouth persists in some of her grandchildren–recognizable. Grandmother Wilson never failed to look up smiling, singing out “Ah, Johnny” when I surprised her at her work. Her griddle cakes were a specialty, and her deep, tangled back yard, rising steeply up the slope of Mount Jefferson was our jungle. She lived beyond 86, dying at about the time I reached my majority.

Joseph and Margaret Farquhar educated their son John, your great-great grandfather, for the ministry. He graduated from Lafayette College in 1841, taught a while, graduated from Princeton Theological Seminary in 1846 (I have his diploma, autographed by the Alexanders and others of the Faculty), married Sarah Wilson, daughter of Alexander and Margaret, and went for his first and only charge to Chanceford Church which he served until his death. He was stricken in the pulpit and died several weeks later on September 18, 1866. He was a man of scholarly tastes, but no recluse. A lover of Dickens and the poets with Burns at the head. I recall faintly his delight in Pickwick Papers, which he watched for eagerly as it appeared, and his hearty laugh over it with my mother and visiting fellow clergymen. He was thoroughly grounded in the use of the English language, and possessed a bent and taste for it. He was an eloquent, able and sincere expounder of the Calvinistic theology. His library was small, but well selected. Beside theological works it comprised Hume, Gibbon, Darwin, Burns, Scott and others attesting both his taste and breadth. A strong Union man in the Civil War, he prayed for the success of the Union arms, and was rescued from assault for it attempted by copperheads among his listeners in that region close to the Maryland line. He had plenty of Scottish determination (to call it no other) and was know to have displayed in clerical assemblies. Developing artistic tastes, he studied drawing under a teacher, and left remarkable portraitures of my mother, himself and others, done in fine-pointed lead pencil. He was sporting enough, I have always like to know, out of an attenuated salary, and in spite of Scottish thrift and Calvinistic inhibitions, to pay ten dollars to hear Jenny Lind. His hobbies, beside drawing, were raising fruits, photography, preserving collections of snakes, butterflies and beetles. He designed and colored the mourning decorations for the church upon the assassination of Lincoln (the news of which I vaguely remember arriving when I was four). He was of middle height, solidly built and, like a Scot, was sandy of skin, beard and hair. His sermon on the death of Lincoln, printed by request of his congregation, embodies an appraisal of the martyred President remarkable in accord with that of history. The sermon searches history almost in vain for so foul a deed, and instances the murder of Henry of Navarre, drawing from the later even enumerated lessons appropriate to the tenets of the speaker. An elevated performance throughout. I remember my fathe’s death bed, from which his last words were addressed to me, then 5 1/2.

His wife, Margaret Wilson’s daughter, my mother, your great-great grandmother, was left a rural clergyman’s widow at the age of 43, with no greater means than was to be expected in the circumstances, with five children, the oldest in college. She educated them by taking boarders from among the college students at Easton from 1868 to 1882. With the unfailing help of two stanch daughters, Harriet and Margaret, and an incompetent servant or none, she accomplished this without interrupting her attendance (or her daughters’) at church twice on Sunday, and her own attendance at midweek prayer meeting, afoot, 3/4 of a mile each way, half of it steep. During my last two years in college she added to this reading to me for dictation while I was qualifying myself as a shorthand reporter. The religious training of her children could not have been looked after more conscientiously, certainly not more wisely, had my father survived. My mother taught us the Shorter Catechism and made us understand it to the bitter end, even to “What is Effectual Calling?” Here are two Bibles inscribed respectively to my sister Margaret, my elder by five years, and myself (by our Sunday School Superintendent, the late Edward J Fox, Sr., Esq.) “as a prize for reciting the Shorter Catechism, May 30, 1869.” I have to turn to these Bibles to believe it. Each of us recited the whole, question and answer, over a hundred of them. I was eight years, two months and twenty seven days old. My mother was judicious withal in our religious training, imparting instruction in doctrine, but never enforcing from us professions, or compliance with forms, if too strongly against our bent. She was a woman of the soundest judgment, an ideal clergyman’s wife, commanding the devotion of his congregation which subsists, reciprocated, to the third generation. If there were hard spots for the pastor, the affection of the congregation for his wife eased them. She was soundly educated. Her letters are models. Convinced, like her husband, of the righteousness of the union cause, her devotion to Lincoln knew no bounds. With my father she was present and heard the Gettysburg address. I often heard her say: “I stood at the corner of the platform, and Mr. Lincoln was no further from me than across this room.” Dying in 1906 at the age of 83 she remained bright and interested in life to the last, and since her demise has been justly pronounced “Saint and saintly” by numbers who have volunteered this tribute.

Thomas, your great grandfather, was the eldest of my father’s children. The others were Harriet, Joseph, Margaret, and John, the undersigned.

Thomas graduated from Lafayette College in 1871; married Eliza Bogert of a well-known Luzerne County (PA) family, and had six children, Helen, Sarah, Harold, grandfather of John Adams III to whom among others this letter is addressed, Miriam, and twins John Frederick and Edward Franklin, grandfather of John Franklin and Janet Elizabeth, to whom also this letter is addressed. Thomas was all his life a teacher and superintendent of schools, mainly as Superintendent of Schools at Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. His lifelong regret, I understood, was that financial circumstances did not permit him to become a Presbyterian minister. But of him, as well as of your grandfather and father, and those who succeed you, you will of course have more direct knowledge from other sources.

If anyone knows the current location of the John Farquhar travel diary mentioned above, please contact me. I am eager to read a copy!

Download a PDF of the typed letter transcribed above: 1938 Letter to His Great Grandnephews and Great Grandniece from John Wilson Farquhar

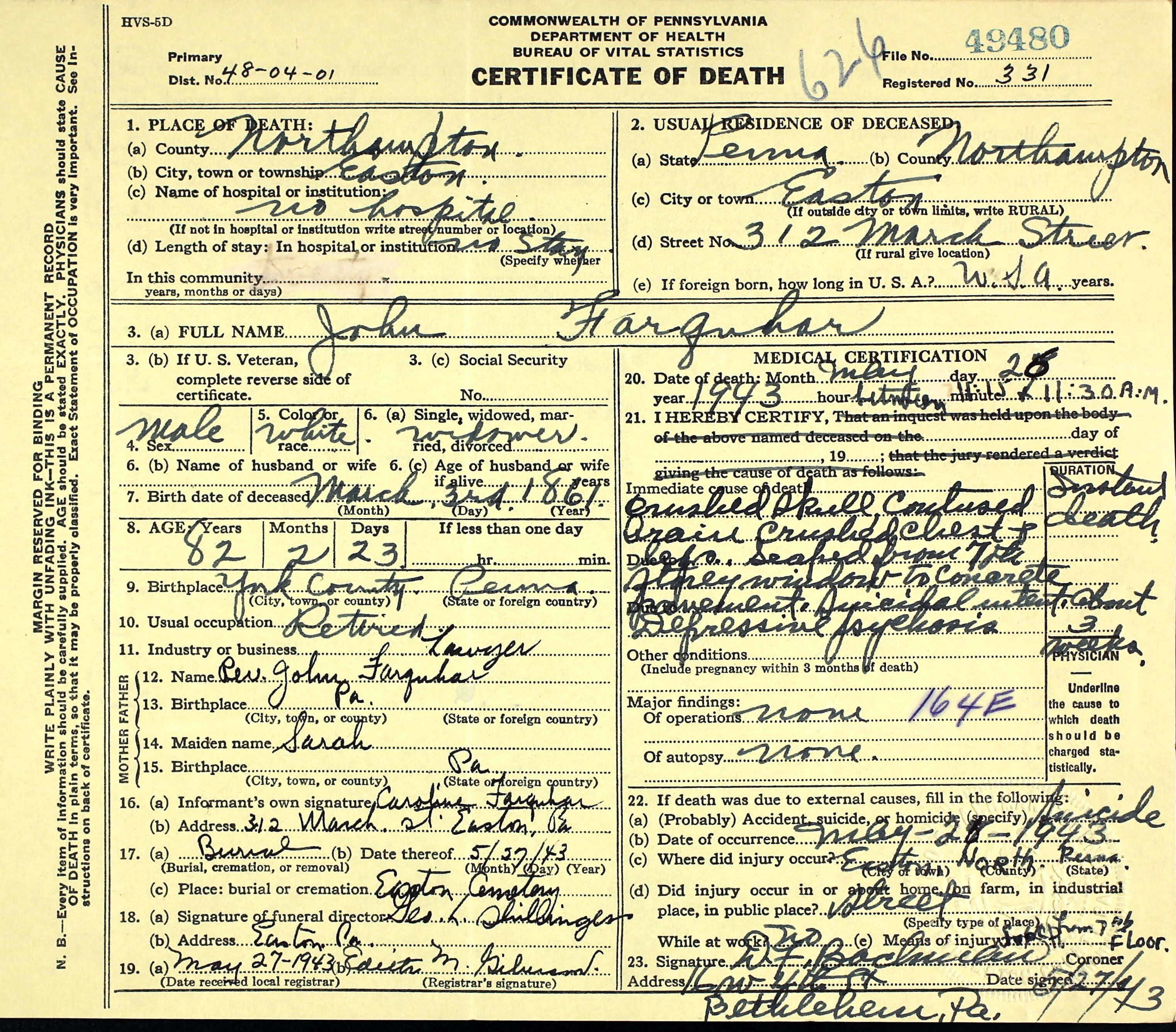

Death By Suicide

Five years after penning this letter, John Wilson Farquhar committed suicide at the age of 82, jumping from the seventh story window of the Northampton National Bank. One paper described the act this way:

An 82-year-old man, John W. Farquhar, graduate of Lafayette College in the class of 1880, and winner of fame and affluence as a member of the New York Bar, came down from his College Hill home by bus yesterday morning, entered the Northampton National Bank building, walked up seven flights of stairs and leaped to his death from the window of the washroom on the 4th Street side of Easton’s tallest office building.

Coroner Dr. D F. Bachman found Farquhar had been suffering from “a nervous upset for several weeks,” and upon conclusion of his investigation of the case the coroner announced last night that Farquhar was a suicide.

Search of the man’s clothing revealed $28.35 in cash, a five-word unsigned note, addressed to Caroline and which read, “I seemed better but was not,” and a laundry mark that was to be of aid to captain of Police H. J. Menikheim in making the identity certain. The note was written on a deposit slip of the Northampton National Bank.

The police inquiry revealed that Farquhar, after alighting from a bus at Northampton and 4th Streets, crossed the street and entered the bank building on the southwest corner. He was seen walking up the steps to the top floor.

Farquhar discarded his tan hat and raincoat before he plunged from the window. Eye-witnesses told of the body striking the cable with such force that it bounded back into the air several feet then dropped to the sidewalk. There was a deep gash in the neck where it came in contact with the stout wire strung between two poles.

For more than an hour the body lay in the street, with Easton police keeping the curious away, pending the arrival of Coroner Bachman from Bethlehem. The coroner ordered the corpse removed to the Adams funeral home on Spring Garden Street. [Lawyer In Death Leap; Unidentified For Hours. The Morning Call, May 27, 1943, pages 1 and 6.]

This account provides us with no clue as to what the troubles were and I have found no explanation for his suicide in family documents. The only thing we can conclude is that the press of fifty years ago was equally as sensationalistic then as it is today.

Trackback 1

TrackBack URL

https://www.karenfurst.com/blog/genealogy/surnames/farquhar/john-wilson-farquhar-1861-1943/trackback/