Immigration of French Huguenots in Berlin in the 18th Century. Woodcut after a contemporary etching (1771) by Daniel Chodowiecki from the book “Deutsche Geschichte (German history)” by L. Stacke (Volume 2). Published by Velhagen & Klasing, Bielefeld and Leipzig, 1881

My line of LeBlonds were French Huguenots and left France in the late 1600’s to escape persecution for their religious beliefs.

- 1509

- John Calvin (1509-1564) born.

- 1550

- The Huguenot Threadneedle Street Church founded in the area of Spitalfields in London.

- 1562

- Massacre at Vassy marks the beginning of the Wars of Religion and the persecution of the Huguenots. Soldiers sent by Francis, Duke of Guise, leader of a Catholic faction, killed many of a congregation of 1200 Huguenots worshipping inside town walls, a forbidden act.

- 1570

- Treaty of Saint Germain

- 1572

- Massacre of St. Bartholomew

In 1572, several thousand Protestants who had come to Paris to attend the wedding of Henry of Navarre and Margaret of Valois, died in the so-called Massacre of St. Bartholomew. On Friday, August 22, 1572, Admiral Coligny was wounded in the hand and arm by a shot fired from a window in the Louvre. Catholic mobs locked the city gates and killed 2,000 to 3,000 Huguenots. Other massacres followed in Bordeaux, Lyons and other cities, killing 10,000 more Huguenots.

Francois Dubois (1529-1584) Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, ca 1572-84, oil on panel, Musee cantonal des Beaux-Arts, Lausanne

- 1573

- Siege of La Rochelle

After the massacres of St. Bartholomew’s Day and others across France in the fall of 1572, numerous Huguenots fled to the largely autonomous and overwhelmingly Huguenot city of La Rochelle, as a last refuge. The city of 20,000 inhabitants was well fortified, with access to the sea; in fact, its port was of strategic importance with historic links to England.The city’s leaders refused to accept a royal governor, sparking conflict with the crown. The six-month siege, led by the future Henry III, the Duke of Anjou, was brought to an end by the signing of the Edict of Boulogne.

- The Peace of La Rochelle / The Edict of Boulogne

– conceded freedom of conscience and a restricted right of worship to Protestants. - 1589

- Henry III (Duke of Anjou) killed by a Catholic fanatic. Although he led the army to besiege La Rochelle in 1573, he later argued that a strong and religiously tolerant monarchy would strengthen the kingdom. Henry III of Navarre succeeded him as Henry IV, the first of the kings of the House of Bourbon.

- 1590

- 1598

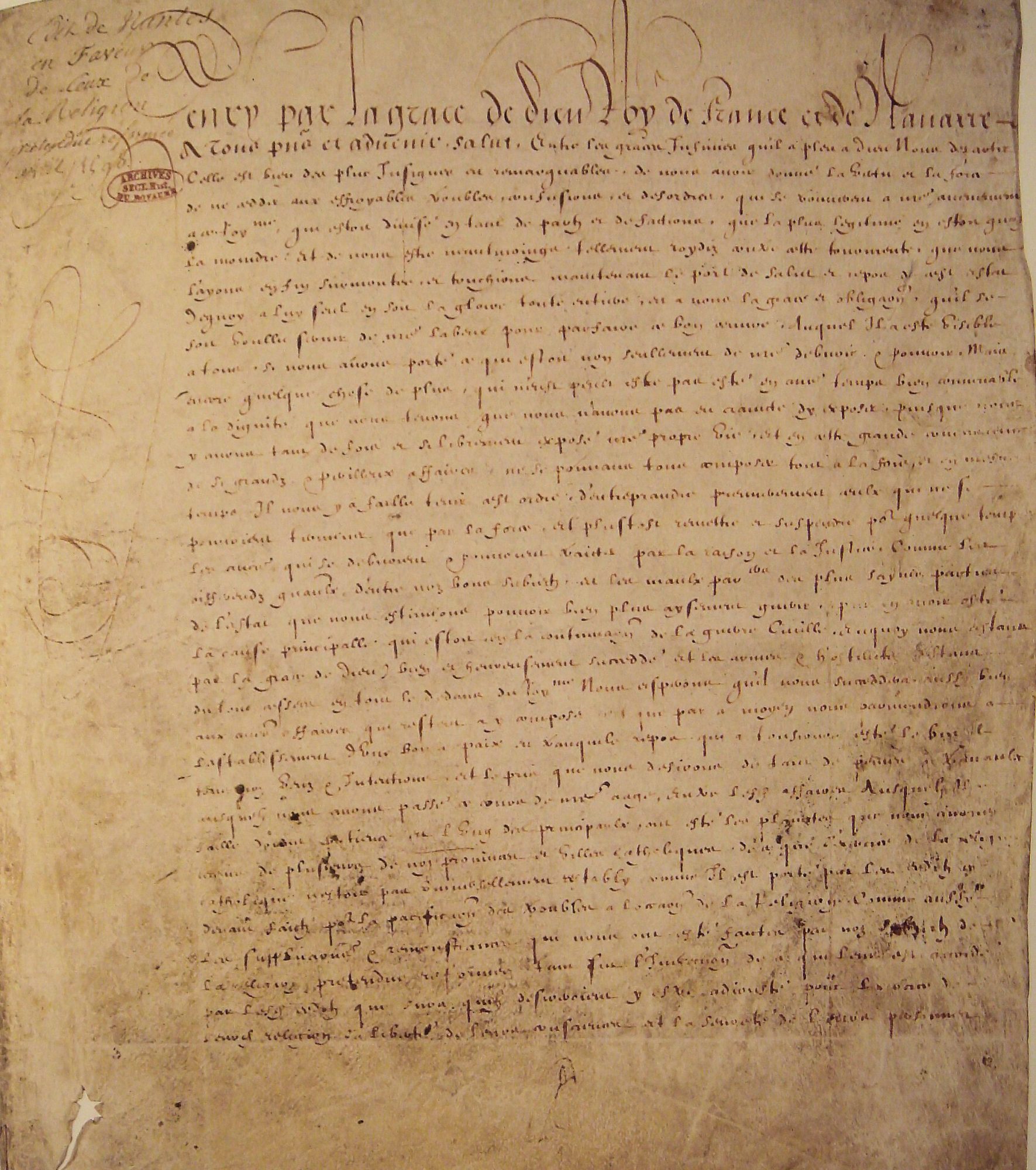

- Edict of Nantes signed by Henry IV, guaranteeing the Huguenots freedom of public worship in 200 fortified towns in France. The edict was supposedly “perpetual and irrevocable.” Protestant worship, previously held in secret, became public as permanent temples were built.

- 1619

- From 1619 the Council of the Huguenots sat regularly at La Rochelle.

- 1625

- Siege of La Rochelle

By 1625, La Rochelle had become the stronghold of the French Huguenots, under its own governance. One of the largest cities in France, with over 30,000 inhabitants, it was the center of Huguenot sea power and the strongest center of resistance against the central government. Changes in the monarchy met with increased Protestant resistance until tensions escalated to the point that Huguenots ensconced in the city revolted under the Duke of Rohan. - 1626

- England declared war on France in support of the Protestants but the British army failed to defeat the French near La Rochelle.

- 1627

- The city was besieged by a Catholic army under Cardinal Richelieu. The siege marked the apex of the tensions between the Catholics and the Protestants in France, and ended with a complete victory for King Louis XIII and the Catholics. Ten thousand of its 25,000 citizens died of starvation in the fourteen-month siege, along with many more from disease and casualties of war.

- 1629

- Peace of Alais / Edict of Alès / Edict of Grace

In this treaty negotiated by Cardinal Richelieu with Huguenot leaders and signed by King Louis XIII of France on 27 September 1629, the basic principles of the Edict of Nantes were reaffirmed, with additional clauses stating that the Huguenots no longer had political rights and further demanding they destroy all their fortifications and relinquish all garrison towns and fortresses immediately. It ended the religious warring while granting the Huguenots amnesty and civil equality and guaranteeing them tolerance and freedom of worship. - 1652

- Louis XIV declared his intention to maintain the Edict of Nantes. However, he gradually increased persecution of them until he issued the Edict of Fontainebleau (1685), ending any legal recognition of Protestantism in France and forcing the Huguenots to convert or flee in a wave of violent dragonnades.

- 1661

- Cardinal Mazarin, who had acted as the Huguenot protector in France, died. Starting in this year, the King sanctioned a series of proclamations which reinterpreted the Edict of Nantes and restricted Protestant worship.

- 1678

- Campaign was underway a convert Protestants.

- 1681

- Protestants in the province of Poitou were forcibly converted to Catholicism. Protestant temples were demolished. Troops were billeted on the Protestant population. (Billeted means for soldiers to live with families who had to support them financially.) The edict encourage children aged seven and above to abjure their faith, leave home, and demand an allowance from their parents.

Charles II of England issued proclamation offering England as place of refuge for Huguenots. Londoners and their countrymen participated in house-to-house collections to aid in the relief of the Huguenot refugees. A soup kitchen was opened in Spitalfields for the Huguenot poor. Charitable groups were established to assist aged Huguenots and paid apprenticeships for the children. (Spitalfields became a French community depended heavily on the weaving trade.)

- 1683

- The King and Françoise d’Aubigné (Madame de Maintenon), the former governess to the king’s illegitimate children, were secretly married.

- 1685

- A petition was presented to Louis XIV stating that the Protestants have been refused admission to public office and have been dismissed from positions of authority in which they had served with honor and fidelity. Protestant children were taken from their homes. The petition pleaded for a return to the observance of the Edict of Nantes, which Louis XIV revoked. The new law ordered the destruction of churches, the closing of schools, the Catholic baptism of Huguenots and the exile of Huguenot pastors who refused to renounce their faith.

Persecution of the French Huguenots (After the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes by Louis XIV in 1685), 1904, Maurice Leloir (1853-1940 French), Color lithograph

Tens of thousands of Huguenots fled to other countries including Holland, England, and Prussia. The Revocation gave Protestant ministers a fortnight in which to leave France, on pain of death or imprisonment if they delayed. Other Protestant subjects caught attempting to leave the country would be condemned to the galleys, if men, or confined to a convent, if women.

- 1700

- By 1700 there were 20,000 to 25,000 Huguenots in the area of modern greater London.

- 1750-1775

- By this date range, all of the Huguenot descendants had assimilated into English culture, abandoning use of the French language.

It is estimated that 200,000 to 250,000 Huguenots left France while 700,000 remained and abjured their faith. Most who left went to the Dutch Republic, then Britain, Germany, Ireland, and the American colonies.

Sources

- Murdoch, T.V. The Quiet Conquest: the Huguenots 1685-1985. London: Museum of London, 1985. DA122.H89* (Winterthur Library)

I have French Protestant ancestors; My maternal grandmother Elizabeth Couser was aware of her Huguenot forebearers who went to Northern Ireland to run a linen mill. My paternal grandmothers maiden name was Agnew, a common name in Ulster. How can I find out more?

Try Ancestry.com – they should have something to help you. Good luck!